TFF ThinkTank | The Dead End of Residency Doctors: The Predicament of Pressure

- Yike Zhang

- Sep 3, 2025

- 5 min read

The Tip of the Iceberg

On February 23, 2024, a residency doctor ended her own life. Her name was Cao Liping. When I read about Cao Liping, the words that stood out to me were “overtime” and “sudden death.” But is this limited only to residency doctors? The medical system itself is also working “overtime.” And the moment the medical system suffers its own “sudden death” is the very moment of its collapse. The death of one individual signals an earthquake within the entire system.

Amateur Moves

The term residency doctor might sound unfamiliar to many. The system of standardized physician training — what we now call residency — first took shape in 19th-century Germany and was refined in 20th-century America. In the U.S., residency programs began in the 1920s and, after nearly half a century of development, became a structured and highly respected model of medical education.

China decided to copy this system. In 2013, the National Health and Family Planning Commission, together with six other ministries, issued the Guiding Opinions on Establishing a Standardized Residency Training System. From then on, all new clinical doctors with at least a bachelor’s degree had to complete three years of standardized training and pass a national exam before they could earn a residency certificate and become fully licensed doctors.

But once transplanted into China’s healthcare environment, the model took on a distorted form. The most glaring gap lies in pay. In the U.S., residents earn an average of $60,000–80,000 a year — enough to live above the poverty line and higher than the average city wage. In China, however, in some non-first-tier cities, residency doctors are paid less than the local minimum wage — sometimes as little as 1,300 yuan (around $180) a month.

But today, the focus isn’t on economics. It’s on the darkest black hole swallowing residency doctors—the crushing weight of pressure.

The Nightmare Begins

The most visible form of this pressure is sheer exhaustion. According to messages posted by resident doctor Cao Liping before she took her own life, her heart rate—139, 142, 144, 149—finally spiked to 152 on her sixth check, all from overwork. This was around 8:30 a.m. on the last Friday of February.

And still, the endless overtime went on. On February 22, she worked until 9 p.m., spending the night in her department. On February 23, after submitting the medical record of one last patient, she ended her life.

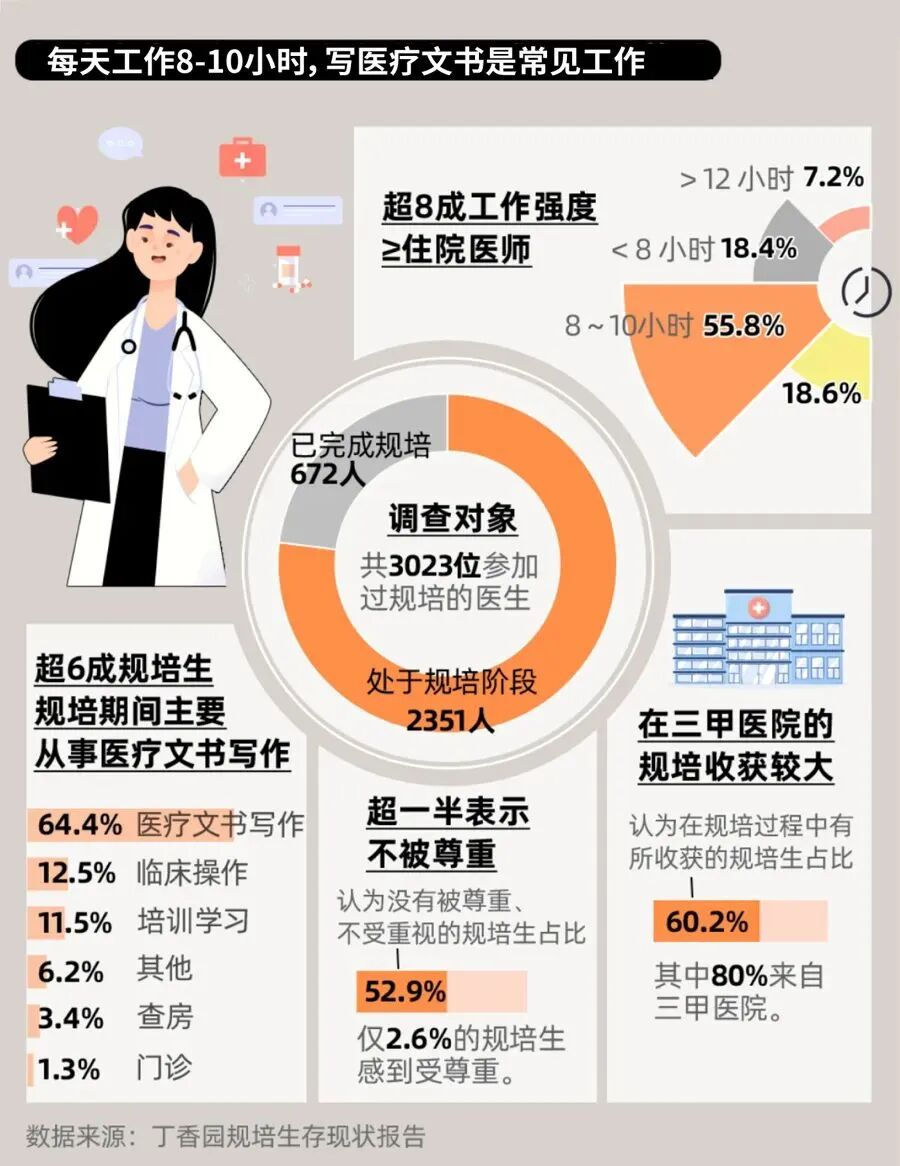

She was not an isolated case. A 2023 survey by the Chinese Medical Doctor Association found that 78.6% of residents work more than 60 hours per week. Another study published in the Chinese Journal of Hospital Management reported that 41.2% of residents show symptoms of depression.

Medical training has always been grueling. But isn’t this a step too far?

Psychological Dead Ends

The pressure isn’t just physical fatigue—it’s the crushing imbalance between effort and reward. Beneath it all is a deeper strain: anxiety, the feeling that your work has no meaning.

One sociological study, Professional Socialization in Transition: Marginality and Conflict in Residents’ Interactions, describes residents as being stuck in a liminal state. They lack the autonomy of attending physicians, yet they don’t enjoy the benefits of full-time employees.

In theory, the pei in “guipei” (standardized training) means education. In practice, countless residents are treated as expendable labor, doing endless menial tasks: copying medical records, printing consent forms, filling out paperwork that requires no thought.

The busier they are, the more hollow they feel.

Dr. Chen Xiaoxi, now an attending physician at a top hospital in Shanghai, once endured the same path. She put it bluntly:

“If you told me to write twenty meaningless case notes in a day, I’d break down. But if I could write twenty difficult tumor cases in a day, and actually scrub into the surgery, even if it killed me with exhaustion—many doctors would still say yes.”

Why Has It Come to This?

The roots of this distorted residency culture lie in two things: a mismatch between supply and demand in healthcare, and deep power imbalances inside hospitals.

On the demand side, rising incomes in rural and remote areas have unlocked previously hidden medical needs. Patients who once went to informal clinics now crowd into big-city hospitals. Add to this China’s rapidly aging population, with soaring rates of chronic illness, and the growing middle class seeking not just treatment but better, more personalized care. All of it funnels into top-tier hospitals already stretched to their limits.

On the supply side, medicine is knowledge-intensive. Training a competent doctor takes a decade or more—undergraduate study, residency, specialty training. The pipeline moves slowly, while demand surges quickly. The result: overloaded hospitals and doctors working beyond capacity. Compounding this, Chinese doctors hold lower social status compared with their peers abroad. As Prof. Wang Hufeng noted in Research on the Efficiency of Medical Resource Allocation (2021), high-quality medical resources are overly concentrated, and social recognition of doctors’ value remains limited. Fewer young people see medicine as a first choice, further constraining the talent pipeline.

This reminds me of Malthusian theory. Population grows exponentially, resources only linearly. Inevitably, demand outstrips supply. In China’s healthcare system, that gap is already yawning wide: demand is skyrocketing while resources crawl forward. Unless this imbalance is addressed, the system will buckle under its own weight, driving more doctors out through stress and low pay, in turn accelerating collapse.

And then there is power. Residents are trapped by structural inequality. For them, the residency certificate is as essential as a diploma—it’s the only ticket to becoming a licensed doctor. The attending physicians who supervise them hold that key. As a result, many residents tiptoe constantly, afraid of being punished or dismissed.

Cao Liping’s final words reflected that fear:

“I’m scared of my supervisor. Afraid of being at her mercy.”

Supervisors, wielding this asymmetric power, often offload repetitive grunt work onto residents. Wang Xiaoli, a peer of Cao’s, recalled her time in residency at Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital:

“Eighty percent of the time was meaningless busywork—copy, paste, type orders. Whether you learned anything depended entirely on your supervisor’s goodwill. If they were too busy, your entire three-month rotation was wasted. Occasionally, if you got a good mentor, you might pick up real skills—but that was rare.”

The result is a gnawing, tentacle-like anxiety. Not just wasted hours, but wasted effort—labor drained of meaning.

And it’s not only about teachers and trainees. Patients themselves often wield the greatest power in hospitals, and many refuse to let residents perform procedures. That leaves residents locked out of critical hands-on experience.

Thus, the vicious cycle: residents face high workload, low recognition—always busy, never advancing.

Where Is the Way Out?

Is there a solution?

On the demand side, one answer once lay in tiered medical care: minor ailments like colds should be treated at clinics, not at overcrowded tertiary hospitals. But as incomes rose and patient choice expanded, this system collapsed, dismissed as a restriction on people’s right to choose their care.

That leaves the supply side. If resources are scarce, they must be used wisely. Residents—an invaluable resource—should not be wasted on low-level chores. Their energy should go into tackling complex cases. But then who handles the repetitive tasks?

Here, technology offers hope. AI is already proving itself. A study by Academician Dong Jiahong’s team, published in Nature Digital Medicine, showed that AI-assisted diagnostic systems can identify liver tumors with 96.5% accuracy. AI can handle routine imaging, pathology, and paperwork, freeing doctors to focus on decisions that require true expertise. Smart health monitoring can catch diseases early, reduce severe cases, and lighten the burden on hospitals.

In other words: let machines do the meaningless work.

If this happens, residents will still be exhausted—but at least their effort will feel worthwhile. Because the most deadly pressure is not overwork. It is emptiness.

Why is a hollow tube so easy to crush? Because it’s empty. One squeeze, and it collapses.

Writer: Georgina Zhang

Editor: Roy Chen

Translation: Christina Zhang

Proofreader: TK

Comments